Utilisateur:Shagada/Femmes architectes

L'Architecture Africaine concerne l'architecture du continent africain, de son origine à nos jours. Conséquemment à la superficie et à la diversité culturelle du continent, son architecture est riche et diverse. Certains styles se dégagent par leur influence et leurs caractéristiques, comme l'architecture sahélienne (architecture du Sahel) en Afrique de l'ouest. Un des éléments marquants et commun à l'architecture traditionnelle est l'utilisation de fractales mathématiques.

Comme toutes les architectures traditionnelles du monde, l'architecture africaine a subis de nombreuses influences antérieures. L'architecture occidentale a aussi eu un impact conséquent sur les zones côtières depuis la fin du XVe siècle, et est une source d'inspiration importante pour les bâtiments modernes, principalement dans les grandes villes.

Early architecture

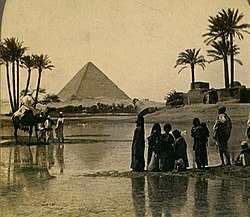

modifierProbably the most famous class of structures in all Africa, the pyramids of Egypt remain one of the world's greatest early architectural achievements, if limited in practical scope and originating from a purely funerary context. Egyptian architectural traditions also saw the rise of vast temple complexes and buildings.

In Nubia we have the Steo carved out of Rocks. By the Meroitic period, houses were of two rooms, forming large complexes. Notable buildings include the Meroitic Western Palace of Faras, built of sun-dried brick.

Little is known of ancient architecture south and west of the Sahara. Harder to date are the monoliths around the Cross River, which has geometric or human designs. The vast number of Senegambian stone circles also evidence an emerging architecture.

Egypt

modifierEgypt's achievements in architecture were varied from temples, enclosed cities, canals, and dams.

Nubia

modifierThe Egyptians had over the centuries attempted to control the Nubians in order to secure the gold from the local mines. Despite being subject to the Egyptians, the Nubians adopted many of the Egyptian customs, mainly as a result of the Nubian men who served in the Egyptian army. In the eleventh century BC, internal disputes in Egypt caused colonial rule to collapse and an independent kingdom arose based at Napata in Nubia. The kingdom was united by Alara (780-755 BC) with the kingdom growing in influence and coming to dominate the Southern Egyptian region. When the Assyrians invaded Egypt, in 671 BC, Kush, as the kingdom was known, became an independent state until 591 BC when the Egyptians under Psamtik II invaded Kush and sacked and burned Napata. Little is left today of the original city, but excavations have brought to light some thirteen temples and three palaces.

In 350 BCE, partially in response to Egyptian pressure, the kingdom’s capital was moved to further south to Meroë, and the city became an important iron producing center. Around 300 BC, the monarchs began to be buried there. The city - on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km northeast of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, ca. 200 km north-east of Khartoum - is marked by over two hundred pyramids of different sizes in three groups. The pyramids were built of sandstone, and ranged from 10 to 30 m in height. Around AD 350 the area was invaded by the Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum and the kingdom collapsed.[1]

Axum

modifierThe best known building of the period in the region is the ruined or eight century BC multi-story tower at Yeha in Ethiopia, believed to have been the capital of D'mt. Ashlar masonry was especially dominant during this period, owing to South Arabian influence where the style was extremely common for monumental structures.

Aksumite architecture flourished in the region from the 4th century BC onward, persisting even after the transition of the Aksumite dynasty to the Zagwe in the 12th century, as attested by the numerous Aksumite influences in and around the medieval churches of Lalibela. Stelae (hawilts) and later entire churches were carved out of single blocks of rock, emulated later at Lalibela and throughout Tigray, especially during the early-mid medieval period (ca. 10th-11th c. in Tigray, mainly 12th c. around Lalibela). Other monumental structures include massive underground tombs often located beneath stelae. Among the most spectacular survivals are the giant stelae, one of which, now fallen (scholars think that it may have fallen during or immediately after erection) is the single largest monolithic structure ever erected (or attempted to be erected). Other well-known structures employing the use of monoliths include tombs such as the "Tomb of the False Door" and the tombs of Kaleb and Gebre Mesqel in Axum.

Most structures, however, like palaces, villas, commoner's houses, and other churches and monasteries, were built of alternating layers of stone and wood. The protruding wooden support beams in these structures have been named "monkey heads" and are a staple of Aksumite architecture and a mark of Aksumite influence in later structures. Some examples of this style had whitewashed exteriors and/or interiors, such as the medieval 12th century monastery of Yemrehanna Krestos near Lalibela, built during the Zagwe dynasty in Aksumite style. Contemporary houses were one-room stone structures or two-storey square houses or roundhouses of sandstone with basalt foundations. Villas were generally two to four stories tall and built on sprawling rectangular plans (cf. Dungur ruins). A good example of still-standing Aksumite architecture is the monastery of Debre Damo from the 6th century.

- Prof. James Giblin, Department of History, The University of Iowa. Issues in African History